For me, one of the most fascinating realms of research is cognition and the physiology of the brain; what is happening in the brain during certain thinking activities. As such, I often find myself in journals which many would probably use as sleep aids: Clinical Neurospychology, Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, and Brain and Cognition. The studies published in these journals often rely upon brain scans, but not just your run-of-the-mill black and white MRI of yesteryear.

Brain scans have come incredibly far (and continue to improve in their depth of detail). Two scan types routinely show up in my research: DTIs and fMRIs. The above image is not a pretty jellyfish, but a DTI scan. In order to understand these scans, let’s start with the basic and most well-known scan: MRI.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), as the name suggests, uses radio frequencies and intense magnetic fields to align the protons in water molecules in order to map the interiors of objects. Though this technique was first discovered in the 1940’s, it was not used for medical purposes until the 1990’s (and is now considered indispensable).

Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI) is an MRI based imaging of the brain that details the neural pathways. Without getting into the medical vernacular, which would require more definitions, the image essentially maps the fiber networks in the brain based upon the molecular movement of water along those fibers, as opposed to the more open areas of the brain. The resultant map also shows the thickness and density of the connections in the brain.

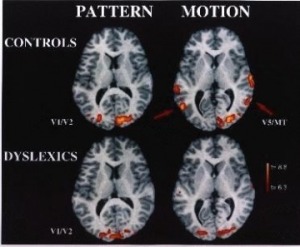

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI), while still utilizing MRI technology, tracks changes in blood flow and oxygen levels, which illustrates neural activity. Essentially, the increased blood and oxygen flow highlights which regions are being utilized during any particular activity.

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI), while still utilizing MRI technology, tracks changes in blood flow and oxygen levels, which illustrates neural activity. Essentially, the increased blood and oxygen flow highlights which regions are being utilized during any particular activity.

Though the use of neuro-imaging in educational and psychological circles was initially met with criticism, subsequent decades of research have highlighted the tremendous potential such developmental and cognitive data brings to educational practice. Specifically, the data has assisted the field of Educational Therapy to fine tune its practices and to further understand issues such as dyslexia, dysgraphia, reading comprehension, and language processing.

I once heard it said that education is the only field where the practitioners do not consult images of the organ with which they work. Neurosurgeons, cardiologists, and gastroenterologists all look at detailed and comprehensive imaging of the areas they masterfully treat. In education, the tendency is to narrow the focus to strictly behavioral considerations.

With 30 years of building research, the tides continue to change and our understanding of academic and even behavioral problems are becoming more nuanced. As a result, our solutions and practices grow more precise.

Though I have only cleared a meager portion of the articles I have marked “to read,” I am challenged, encouraged, and better informed by each one. Now that I have established some basic terminology and information, I look forward to writing about how specific articles have influenced or improved my educational practices.

From the desk,

Mr. Bluebaugh